What building a deck taught me about fluency, patience, and why it’s okay to stay in gear one—for a while.

Setting the Last Screw (Almost)

Ten screws short. Out of 374, just ten left to go. That’s where I found myself—hands dusty, knees sore, the new deck on our tiny house almost complete. And with that, the first phase of this new chapter in tiny living came to a close.

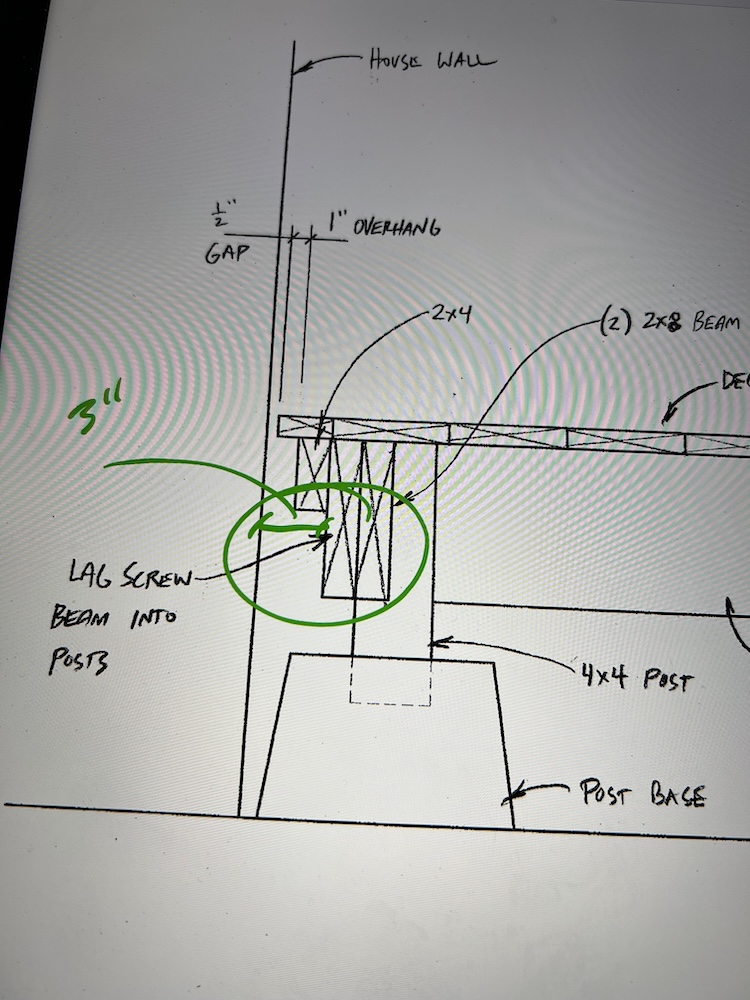

The deck was more than a platform. It was a canvas, a structure marking the transition from just getting by to having a functional, livable space. It was drawn up by my brother-in-law—a structural engineer whose thesis was literally on concrete—and it was solid. His plans were like old-school schematics: follow view A, then view B. Stick to the blueprint, and you’ll be okay.

But, of course, nothing ever goes exactly as drawn.

Learning by Doing (and Asking)

I didn’t grow up with tools in my hand. My mom used to pay the neighbor kid (my best friend) to mow our lawn. And yet, here I was, 374 screws deep into a deck I had built with my own hands. It wasn’t my first project. Years ago, I rebuilt a porch and a deck with borrowed advice and borrowed tools. I learned to cut spindles, reinforce joints. Four years ago I redid the gutted “Estate” and even found out what PEX plumbing was—life-changing, by the way.

This time, I leaned on muscle memory and phone calls. I borrowed a chop saw from my neighbor Ken, who kindly gave me a 45-minute unsolicited inspection and advice session. Some of it was practical (how to clamp a warped board), some of it was life story (his old shop in Florida), but all of it was welcome.

His parting feedback stuck: “It’s not level. But it’s solid.” I’ll take that.

Two Gears, One Lesson

Now here’s the part where a drill becomes a teacher.

On my power drill, there are two settings. One is slow and steady. The other is fast but harder to control. For most of the build, I stayed in gear one—safe, predictable, but slow. Eventually, I tried gear two. The drill bucked, the screw heads stripped. I wasn’t ready. But after about 75 tries, I figured it out: line it up slow, then press through. It wasn’t speed that made it work. It was rhythm, and eventually, feel.

That moment reminded me of writing.

So often we ask students to write as if they’re already in gear two—fast, polished, precise. But most haven’t even learned how to hold the drill yet. We give them rubrics before they’ve built anything. We assess final products when what they need is permission to practice, strip a few screws, and keep going.

The Plateau of Progress

Writing, like construction, like living, takes repetition. You line it up. You engage. You notice. You repeat. And every so often, you reflect. That’s where growth happens—not in the product, but in the doing.

We ask this of runners, of musicians, of artists. Why not of writers?

In his book Mastery, George Leonard writes about the plateau—the long, flat stretch of effort where there’s little visible progress but deep development is happening. Mastery, he argues, isn’t about constant improvement. It’s about learning to love the plateau. To stay with the work when it feels slow and quiet, and to trust that something is being built even when you can’t yet see it.

And that’s the work of writing. Of teaching. Of building anything that lasts.

The Deck, and the Invitation

I did go back and drill in those last ten screws. And with that, the deck was finished. A few weeks earlier, we were using a step ladder just to get into our front door—awkward, temporary, always a bit precarious. Now, with the deck in place, it’s not just an improvement; it’s an extension of our tiny house living. It’s where we now drink coffee, hold conversations, and end our days.

What was once a rough workaround is now part of the structure. And we’ve already forgotten what it felt like not to have it.

That’s the quiet beauty of repetition and rhythm—of staying in gear one long enough to build something real. And maybe that’s the invitation, too.

Not just for ourselves, but for others: to give space for slow starts, uneven progress, and gradual confidence. To trust that fluency follows practice. That over time, what feels like effort becomes ease—and what once felt temporary becomes part of how we live and work.