On setbacks, endurance, and the next move we can still make

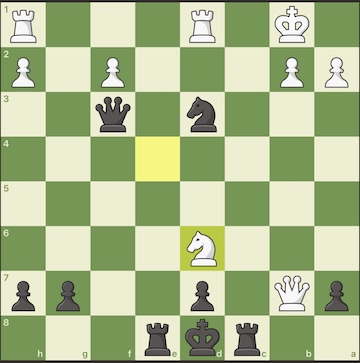

Evan and I have played chess together since he was barely out of toddlerhood. I have a photo of him, maybe three years old, already knowing how to move the knight—the horsey, as he called it. That early joy launched years of games. Tournaments, wins, losses. Sometimes he beat me; sometimes I held my own. But always, we came back to the board. Because it wasn’t about ranking or mastery. It was about the practice. About what the game invites you to see.

Recently we played online. I made a move that took his queen. I didn’t do it recklessly—he had a knight that could take me back. I figured he’d see it, trade the knight for the queen, and the game would continue. But he didn’t see it. And he resigned. Just like that. I remember messaging him: “Dude, you shouldn’t have resigned. It wasn’t over.”

Because it wasn’t. The board was still there. Pieces still in play. But the moment felt too big. The setback felt like the end, because in chess, if you lose your most powerful piece–the Queen–all seems lost.

And isn’t that how it goes? Setbacks feel final when you’re in them.

I see it in myself. Take my running shoes, for example. I’ve run for years, and like anyone in a sport, you find yourself getting attached to certain gear. For me, it wasn’t about flashy outfits—most of my race shirts came from the events themselves—but shoes were a different story. I learned early, after some painful missteps, that long-distance running isn’t kind to shoes that don’t fit right. My first marathon taught me that lesson the hard way: I needed shoes at least a half size bigger to accommodate swelling. So I went to a proper running store, learned about gait and pronation, and settled on Asics. A stable, reliable shoe that served me well for over a decade. Same model, year after year. I’d write the date on the side of the shoe to track when it was time for a new pair—about every 500 miles or so. And then, they changed the model. The fit wasn’t right anymore. Too tight. I don’t have especially wide feet, but they felt wrong. I switched brands—now I run in Brooks—but every so often, I look at Asics again, wondering if I can just get back to that perfect fit. That if I could, everything else would click too.

And then there’s the Gatorade bottles. I used to rely on those 24-ounce sport cap bottles for my long runs. Not because I’m a big Gatorade fan—I’d usually dump out the drink and fill the bottle with water—but because the size was perfect. The grip, the cap, the durability. They’d last me an entire season for just a couple bucks. But lately, I couldn’t find them. I checked every gas station, every convenience store, and eventually turned to Amazon, where I ended up with a strap but no bottle. It felt absurd, how much energy I was spending trying to replace this small, familiar tool. Then, one day back in Indiana, I spotted a single bottle on a bottom shelf at a gas station. I grabbed it without hesitation. The next time I stopped in, they had a whole row of them, and I bought two—just two—because Lori gently reminded me not to start hoarding. A kind reminder that the comfort of familiar things can turn quickly into clinging.

But here’s the realization that keeps returning—because life keeps making me relearn it.

I’ve written before about the trail mix I hoarded on hikes, as if carrying more would protect me. About the Indiana weather I grumbled about, as if complaining would change it. I named those moments. I tried to draw lessons from them. And yet, here I am again. Shouldn’t I have learned that by now? Shouldn’t writing about it have sealed the wisdom in place? When I find myself grasping again, or complaining again, doesn’t that mean I’ve failed?

That’s the trick the mind plays. The voice that says: You should have mastered this already. That frames every setback as weakness, every lapse as proof of character flaw. That whispers: If you were strong enough, you wouldn’t need to relearn. And so the stumble isn’t just a human moment—it becomes shame. The internal voice flails: You’re weak. You fell off the wagon. You failed.

It’s the same voice behind New Year’s resolutions. The one that says habits are binary: you’re either winning or you’re not. That if you slip, you might as well quit. And it hurts—not just the slip itself, but the judgment we pile on top.

But that isn’t how life works. The world doesn’t run on streaks. The chess game with Evan reminds me: the setback feels massive. The queen is gone. All is lost—or so it seems. But the board is still there. The game isn’t over. The loss is part of it. The unexpected, the humbling, the hard moments—they’re part of it.

Maybe that’s the deeper truth. Life isn’t about keeping a perfect chain of wins, or habits, or good weather, or smooth runs. Setbacks don’t signal failure. Victories don’t buy immunity. The monsoon at Casa Saguaro isn’t good or bad—it’s rain. The humidity in Indiana isn’t punishment—it’s what makes things green.

And I think of Chess: The Musical–that concept album that I was introduced to in Jeff’s dorm room, 1985. How Tim Rice and his team revised it again and again. Thirty or so years of versions, until they could finally say: “I think at last, were getting it right we’ve finally we got it right.” Maybe that’s the point. Not perfection, not over-optimism—but the steady work of staying in the game.

Maybe the task is to stop sorting everything into good and bad, success and failure. Maybe it’s simply to notice: This is it. This is the present moment. Not as proof of worth or weakness, but as part of the rhythm. Ebb and flow. Sun and storm. Shoes that fit, and shoes that don’t. Queens lost, and games still worth playing.

And maybe it’s not about fixing or qualifying or labeling. Maybe it’s about saying less. Expecting less of perfection. And living in this imperfect, still-beautiful present.