The Fog I Built—and the Home That Cleared It

The Illusion of Expertise

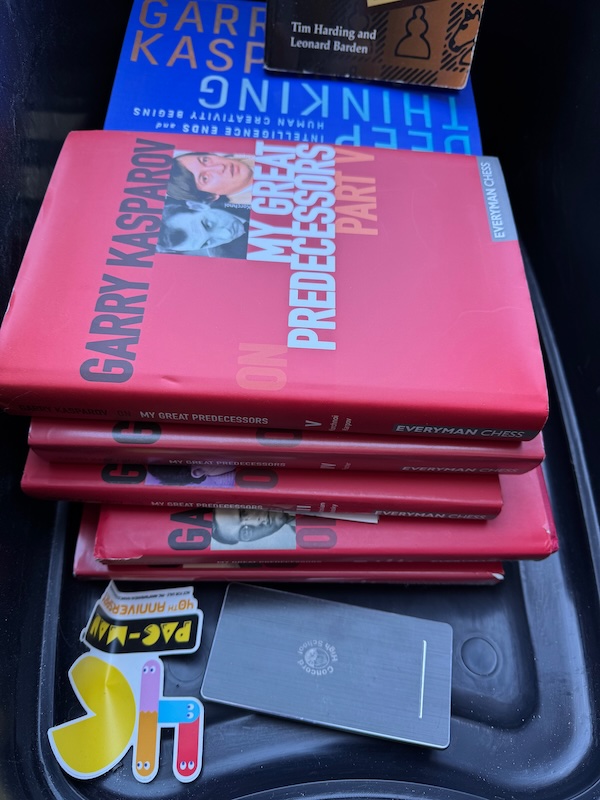

Years ago, I was deep into a chess phase—not competing, not training, but consuming. I’d walk into bookstores and head straight for the games shelf: How to Play Good Opening Moves, Chess: Tactics and Strategies, The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played, Reassess Your Chess (workbook), and the partial set of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors (Volumes 1–5) — I bought them all.

Not because I was studying them. But because I liked what they represented.

They weren’t the only books I collected.

There was the stack of programming manuals I never coded from. The shelf of leadership texts I never annotated. The volumes of Latin primers, teaching strategy guides, and dusty theological tomes I didn’t so much read as arrange. Together, they formed a kind of curated projection: a library not of mastery, but of intention. A portrait of the expert I wanted others to assume I already was.

It felt productive. Almost noble.

But really, it was a well-organized fog.

What I was chasing wasn’t growth—it was identity. Or at least, the appearance of it. And the more I surrounded myself with those titles, the more I mistook proximity for fluency.

This wasn’t a hunger for depth. It was a fear of not knowing enough. And instead of clarity, I got clutter.

The Weight of Too Much

My time in the desert—at Casa Saguaro, where the tiny house lives among the quail, cholla, desert wrens, and the occasional curious coyote—was a kind of transition.

For seven years, I’d worked in a position that centered on coaching teachers. I’d observe classrooms, offer feedback, and help shape instruction to align with larger goals. That work often brought me face to face with pacing guides—local, state, national—that tried to do everything: every writing mode, every reading skill, every test target. Nothing could be left behind.

Even in my current contract work during these desert months, the story hasn’t changed much. I still find myself reviewing state standards and curriculum maps that aim to cover it all. There’s a quiet pressure there, one that builds up like sand in a boot: teachers feel like they have to “cover” everything, “teach” everything. But at what cost?

And what about the students?

Are they tracking all of these targets? Or are they, too, buried beneath the weight of expectations they never asked for?

I’d come home to our tiny house—every square inch accounted for—and unpack the day while slipping off my shoes at the door. Maybe I’d set down something new I’d ordered off Amazon. A book. A tool. A kitchen gadget. And Lori would ask, not unkindly:

“Okay, where’s that going to go?”

That question grounded me.

Because it wasn’t just about space. It was about purpose. If something came in, something else had to go. If we didn’t know where it would live, it didn’t belong.

Meanwhile, in schools, we kept adding. More standards. More systems. More strategies. And almost never asking:

“Where does that go?”

If our homes can’t handle excess without tension, why do we expect our classrooms to?

Living With Less, On Purpose

This is why the Tiny House metaphor keeps showing up for me—not just in teaching, but in how I try to live and lead.

It’s not about asceticism or trend-chasing. It’s about design. About limits that sharpen purpose.

In a tiny house, you don’t keep every book—you keep the ones you actually read. The ones you return to. You don’t arrange a life to look impressive. You arrange it to function.

It applies in every role we hold.

Leaders? Clear space for clarity, not control.

Parents? Choose connection over activity.

Writers? Trade productivity for presence.

The Tiny House isn’t about less for the sake of less. It’s about honest alignment—between who we are and what we carry.

So maybe the question isn’t “What could I add?”

Maybe it’s: “What have I already carried too long?”

Because once the fog lifts, the essentials feel like air again.

The Shelf Doesn’t Have to Be Full

I started this post with a quiet confession: I want it all. Like the Queen lyric—I want it all, and I want it now.

That desire doesn’t come from ego. I think it comes from the anxiety of missing something important. That if I just had one more book, one more strategy, one more piece of information—I’d be ready.

But most of us aren’t suffering from a lack of input. We’re just trying to breathe through the smog.

David Shenk named it back in the 90s: Data Smog—a fog of good intentions, where more content becomes less clarity. And in our classrooms, our inboxes, our libraries, and our lives, we keep inhaling it, hoping something will click.

But maybe clarity doesn’t come from reaching for more. Maybe it comes from reaching for less, on purpose.

So here’s the handoff:

What would it look like this week to live just one step closer to the tiny house?

Not to throw everything out—but to carry less with more care.

Not to prove you’re fluent—but to show up with focus.

The shelf doesn’t have to be full to say something meaningful.